Download the newsletter here.

1) CNIL SANCTION: COMPANY SAF LOGISTICS FINED 200,000 EUROS

On 18 September 2023, the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) fined the Chinese air freight company SAF LOGISITIC €200,000 and published the penalty on its website.

The severity of this penalty is justified by the seriousness of the breaches committed by the company:

- Failure to comply with the principle of minimisation (article 5-1 c of the GDPR): the data controller must only collect data that is necessary for the purpose of the processing. In this case, the company was collecting personal data on members of its employees’ families (identity, contact details, job title, employer and marital status), which had no apparent use.

- Unlawful collection of sensitive data (article 9 of the GDPR) and data relating to offences, convictions and security measures (article 10): in this case, employees were asked to provide so-called sensitive data, i.e. blood group, ethnicity and political affiliation. As a matter of principle, the collection of sensitive data is prohibited. By way of exception, it is permitted if it appears legitimate with regard to the purpose of the processing and if the data controller has an appropriate legal basis, which was not the case here. Furthermore, SAF LOGISITIC collected and kept extracts from the criminal records of employees working in air freight, who had already been cleared by the competent authorities following an administrative enquiry. Therefore, such a collection did not appear necessary.

- Failure to cooperate with the supervisory authority (Article 31 of the GDPR): The CNIL also considered that the company had deliberately attempted to obstruct the control procedure. Indeed, SAF LOGISITIC had only partially translated the form, which was written in Chinese. The fields relating to ethnicity or political affiliation were missing. It should be noted that a lack of cooperation is an aggravating factor in determining the amount of the penalty imposed by the supervisory authority.

2) THE CONTROLLER AND THE PROCESSOR ARE LIABLE IN THE EVENT OF FAILURE TO CONCLUDE A DATA PROTECTION AGREEMENT

On 29 September 2023, the Belgian Data Protection Authority (DPA) issued a decision shedding some interesting light on (i) the data controller’s and processor’s obligations and the late correction of the GDPR breaches. In this regard, the ADP stated that:

- Both the controller and the processor have breached the provisions of Article 28 of the GDPR by failing to enter into a data protection agreement (DPA) at the outset of data processing. The obligation to enter into a contract or to be bound by a binding legal act falls on both the controller and the processor and not on the controller alone.

- The retroactive clause provided for in the DPA does not compensate for the absence of a contract at the time of the event: only the date of signature of the DPA should be taken into account to determine the compliance of the processing concerned. The ADP pointed out that allowing such retroactivity would allow companies to avoid the application of the obligation outlined in Article 28.3 of the GDPR over time. However, the GDPR itself provided for a period of 2 years between its entry into force and its entry into application for gradual compliance by all the entities concerned with a view to guaranteeing the protection of data subjects’rights.

3) A NEW COMPLAINT HAS BEEN LODGED AGAINST THE OPENAI START-UP BEHIND THE CHATGPT GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM

The Polish Data Protection Office has opened an investigation following the filing of a complaint by Polish researcher Lukasz Olejnik against the start-up Open AI in September 2023. The complaint highlights the chatbot’s many failings to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Breaches of the GDPR raised by the complaint

The complaint identifies numerous breaches of the GDPR, including a violation of the following articles:

- Article 5 on the obligation to ensure data accuracy and fair processing (there is an obligation to limit the purposes);

- Article 6 on the legal basis for processing;

- Articles 12 and 14 on information for data subjects;

- Article 15 on the data subject’s right of access to information on the processing of his or her data;

- Article 16 on the right of data subjects to rectify inaccurate personal data.

The legitimate interests pursued by OpenAI hardly seem to outweigh the invasion of users’ privacy.

Repeated complaints against OpenAI

This is not the first time that ChatGPT has been the target of such accusations since it went online. Eight complaints have been lodged worldwide this year for breaches of personal data protection. These include:

- The absence of consent from individuals to the processing of their data

- Inaccurate data processing

- No filter to check the age of individuals

- Failure to respect the right to object.

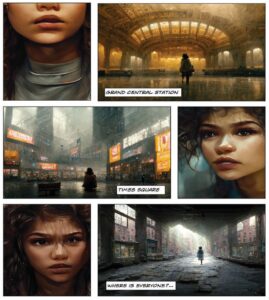

The “scraping” technique used by this artificial intelligence (a technique that automatically extracts a large amount of information from one or more websites) was highlighted by the CNIL back in 2020 in a series of recommendations aimed at regulating this practice in the context of commercial canvassing. These inspections led the CNIL to identify a number of breaches of data protection legislation, including :

- Failure to inform those targeted by canvassing ;

- The absence of consent from individuals prior to canvassing;

- Failure to respect their right to object.

Towards better regulation of artificial intelligence?

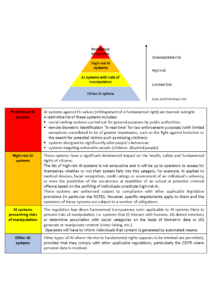

In April 2021, the European Commission put forward a proposal for a regulation specifying new measures to ensure that artificial intelligence systems used in the European Union are safe, transparent, ethical and under human control. The regulation classifies systems as high risk, limited risk and minimal risk, depending on their characteristics and purposes.

Pending the entry into force of this regulation, the CNIL is working to provide concrete responses to the issues raised by artificial intelligence. To this end, in May 2023 it deployed an action plan designed to become a regulatory framework, the aim of which is to enable the operational deployment of artificial intelligence systems that respect personal data.

Repeated complaints against OpenAI

This is not the first time that ChatGPT has been the target of such accusations since it went online. Eight complaints have been lodged worldwide this year for breaches of personal data protection. These include:

- The absence of consent from individuals to the processing of their data

- Inaccurate data processing

- No filter to check the age of individuals

- Failure to respect the right to object.

The “scraping” technique used by this artificial intelligence (a technique that automatically extracts a large amount of information from one or more websites) was highlighted by the CNIL back in 2020 in a series of recommendations aimed at regulating this practice in the context of commercial canvassing. These inspections led the CNIL to identify a number of breaches of data protection legislation, including :

- Failure to inform those targeted by canvassing ;

- The absence of consent from individuals prior to canvassing;

- Failure to respect their right to object.

Towards better regulation of artificial intelligence?

In April 2021, the European Commission put forward a proposal for a regulation specifying new measures to ensure that artificial intelligence systems used in the European Union are safe, transparent, ethical and under human control. The regulation classifies systems as high risk, limited risk and minimal risk, depending on their characteristics and purposes.

Pending the entry into force of this regulation, the CNIL is working to provide concrete responses to the issues raised by artificial intelligence. To this end, in May 2023 it deployed an action plan designed to become a regulatory framework, the aim of which is to enable the operational deployment of artificial intelligence systems that respect personal data.

4) TRANSFER OF DATA TO THE UNITED STATES

On 10 July 2023, the European Commission adopted a new adequacy decision allowing transatlantic data transfers, known as the Data Privacy Framework (DPF).

Since 10 July, it has therefore been possible for companies subject to the GDPR to transfer personal data to US companies certified as “DPF” without recourse to the European Commission’s standard contractual clauses and additional measures.

It should be noted that the United Kingdom has also signed an agreement with the United States on the transfer of data, which will come into force on 12 October.

As a reminder, on 16 July 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) invalidated the Privacy Shield, the previous adequacy decision allowing the transfer of personal data to the United States.

1)The content of the Data Privacy Framework

The decision of 10 July 2023 formalises a number of binding guarantees in an attempt to remedy the weaknesses of the Privacy Shield, which was invalidated two years earlier.

a)The new obligations

In order to benefit from this new framework and receive personal data from European residents, American companies will have to :

- Declare that you adhere to the DPO’s personal data protection principles (data minimisation, retention periods, security, etc.).

- Indicate a certain amount of mandatory information: the name of the organisation concerned, a description of the purposes for which the transfer of personal data is necessary, the personal data covered by the certification and the verification method chosen.

- Formalise a privacy policy in line with the CFO principles and specify the type of relevant independent recourse available to primary data holders, as well as the statutory body responsible for ensuring compliance with these principles.

On Monday 17 July, the US Department of Commerce launched the Data Privacy Framework website, offering companies a one-stop shop for signing up to the DPF and listing the companies that have signed up.

Participating US companies must conduct annual self-assessments to demonstrate their compliance with the DPF requirements. In the event of a breach of these principles, the US Department of Commerce may impose sanctions.

It should be noted that companies already affiliated to the Privacy Shield are automatically affiliated to the DPF provided that they update their privacy policy before 10 October 2023.

- b) The creation of a Data Protection Review Court

The DPF is innovative in that it establishes a Data Protection Review Court (DPRC) to provide EU residents with easier, impartial and independent access to remedies, and to ensure that breaches of the rules under the EU-US framework are dealt with effectively. The Court has investigative powers and can order binding corrective measures, such as the deletion of illegally imported data.

- c) A new appeal mechanism for EU nationals

The planned appeal mechanism will operate at two levels:

- Initially, the complaint will be lodged with the competent national authority (for example, the CNIL in France). This authority will be the complainant’s point of contact and will provide all information relating to the procedure. The complaint is forwarded to the United States via the European Data Protection Committee (EDPS), where it is examined by the Data Protection Officer, who decides whether or not there has been a breach.

- The complainant may appeal against the decision of the Civil Liberties Protection Officer to the DPRC. In each case, the DPRC will select a special advocate with the necessary experience to assist the complainant.

Other remedies such as arbitration are also available.

2) Future developments: new legal battles?

This new legal framework will be subject to periodic reviews, the first of which is scheduled for the year following the entry into force of the adequacy decision. These reviews will be carried out by the European Commission, the relevant American authorities (U.S. Department of Commerce, Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Department of Transportation) and by various representatives of the European data protection authorities.

Despite the introduction of these new safeguards, the legal response has already taken place.

On 6 September 2023, French MP Philippe Latombe (MoDem) lodged two complaints with the CJEU seeking the annulment of the DPF.

Max Schrems, president of the Austrian privacy protection association Noyb, which brought the actions against the previous agreements (Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield), is likely to follow suit.

5) ISSUES SURROUNDING THE MATERIAL SCOPE OF THE GDPR

A divisive position by an Advocate General concerning the material scope of the GDPR could, if followed by the CJEU, clearly limit the application of the GDPR to many sectors of activity (Case C-115/22).

In this case, the full name of an Austrian sportswoman, who had tested positive for doping, was published on the publicly accessible website of the independent Austrian Anti-Doping Agency (NADA).

The sportswoman has asked the Austrian Independent Arbitration Commission (USK) to review this decision. In particular, this authority questioned the compatibility with the GDPR of publishing the personal data of a doping professional athlete on the Internet. A reference for a preliminary ruling was therefore made to the CJEU.

The Advocate General considers that the GDPR is not applicable in this case insofar as the anti-doping rules essentially regulate the social and educational functions of sport rather than its economic aspects. However, there are currently no rules of EU law relating to Member States’ anti-doping policies. In the absence of a link between anti-doping policies and EU law, the GDPR cannot regulate such processing activities.

This analysis is based on Article 2.2.a) of the GDPR, which states:

“This Regulation shall not apply to the processing of personal data carried out :

a)in the context of an activity that does not fall within the scope of Union law;”.

The scope of the Union’s intervention is variable and imprecise, leading to uncertainty as to its application to certain sectors.

In the alternative, and assuming that the GDPR applies, the Advocate General believes that the Austrian legislature’s decision to require the public disclosure of personal data of professional athletes who violate anti-doping rules is not subject to a proportionality test under the terms of the regulation.

However, the Advocate General’s conclusions are not binding on the CJEU. The European Court’s decision is therefore eagerly awaited, as it will clarify the application of the GDPR.

1Last March, the Italian CNIL went so far as to temporarily suspend ChatGPT on its territory because of a suspected breach of European Union data protection rules.

OpenAI failed to implement an age verification system for users. Following on from this event, on 28 July a US class action denounced the accessibility of services to minors under the age of 13, as well as the use of “scraping” methods on platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat and even Microsoft Teams.

2Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence